Dubstep Speaks to Me

I’d been mostly focused on the fish taco in my hand as my friend Ed had been expounding upon his latest lament. Something about an article he’d recently read about the changing cultural practices in another country — Romania or Lithuania, one of the “-anias,” anyhow — and how this one rural village was the last of an entire people to still wear the traditional folk garb. He followed his casual report with, “Isn’t that sad?”

At this, I set what was left of my taco onto the plate in front of me and gave Ed a quizzical glance. “Why would that be sad?”

Now it was Ed’s turn to look confused. “Because these people — their way of life is dying out,” he said. “Only the older generation still wears the garments. Those clothes are part of their identity. If the younger people won’t adopt that, they’re losing a part of their heritage.”

“So?”

The look on Ed’s face could only be described as aghast. His eyebrow twitched. “How can you not care about this? The culture is endangered. Soon it will be extinct.”

“Jesus, the people aren’t dying,” I said. “And the culture isn’t going extinct — it’s adapting. It’s evolving. It’s changing. That’s life.”

In his attempt to get me to see the severity of the situation, Ed started throwing out hypotheticals. “How will we learn the lessons each culture has to teach us?” Easy, I explained, careful documentation and museum tours. Then he made it personal: “How would your parents feel if you suddenly shunned every tradition, ritual, or custom they held dear?”

“Ah, but I’ve already done that,” I said. “It’s possible to love and respect your parents without completely mimicking their way of life. I was raised Catholic, I even went to Catholic school for a bit. But now I don’t even celebrate Christmas. I still get together with my family, we still have other, secular traditions we can all enjoy together. The world hasn’t ended. At least, not yet.”

“I feel bad for your parents,” Ed said. I ignored that; I took a moment to finish my last bite and listened as he continued, “I just think it’s sad that urbanization and our so-called modern ‘advancements’ are snuffing out cultural traditions.”

“Those people don’t have to change if they don’t want to,” I said. “I would feel differently if a population were forced to abandon their way of life, as with the Native Americans or the Jews. That’s just straight-up wrong. But a generation of people who are gradually choosing to adjust their ways to better suit their chosen, changing lifestyles? Why is that sad?”

“I told you — because people will lose their sense of identity.”

“They are not losing their identity. They just have a unique identity that may differ from their parents, grandparents, and so on. Are you suggesting everyone should dress like their ancient ancestors? Next thing you’re going to say is that we should all be wearing togas and owning slaves.”

I’m not a traditionalist. I don’t revere the past. I think my friend’s advanced grief over future change had more to do with nostalgia than anything else. We’re silly if we think we can hold on to any one piece of experience. Things fade. Nothing is forever. Why would we want it to be?

My minor dispute with Ed reminded me of a heated argument David had had with him a few months before, wherein they disagreed about the fate of classical music. Ed insisted that classical music will still be alive and well 100 years from now, but David said it will have faded into history by then. “If you were to ask random 20-somethings to name as many classical composers as they could, I doubt most of them would get beyond Beethoven and Mozart,” David said. “And even then, if they were able to conjure up some names, they’d be unlikely to know any specific works. Ask a kid about the latest hit from Daft Punk, however, and he’ll probably know it.”

Ed said he couldn’t imagine a world where the greats of classical music no longer stood upon their bright pedestals. David said they may still be standing on pedestals, but those pedestals would be situated in a neglected corner of the music world, where the weeds grew high and only the occasional nostalgic listener stopped by to visit.

“Look, I love classical music,” David insisted. “But that doesn’t mean everyone else has to. Everybody chooses what they find to be of value, and each generation is going to value different things, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Why would you think that some future kid living in the year 2100 is going to care about music that was relevant 500 years before?”

Ed was nearly apoplectic. “Because those composers were GENIUSES!”

“Genius isn’t limited to 500 years ago; each generation has its geniuses,” David retorted. “Classical music isn’t superior, it’s just different, and it’s not necessarily relevant to modern generations. And that’s okay — other types of music speak to them more.”

“Dubstep speaks to me,” I interjected, only to get a glare from both men, who had obviously forgotten I was sitting there.

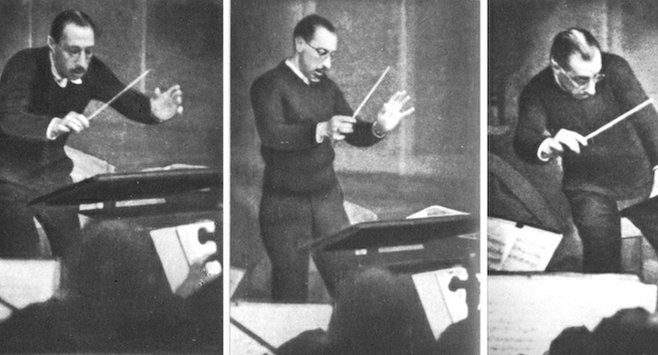

David continued, as if he hadn’t heard me. “I notice that, when you talk about ‘classical music,’” he said, using air quotes, “you limit yourself to composers of a specific era. Why aren’t you exulting the genius of the ancient Greek composer Limenius? Should we all be listening to his music?” Ed rolled his eyes, but David was unfazed. “When Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring first played in 1913, it caused a riot because no one had ever seen or heard anything like it. It was the dubstep of its day. And now it’s hailed as a masterpiece.” Ah, so he did hear me, I thought, and smiled.

“Don’t forget opera,” I said. “Opera is dying.”

“And that’s terrible,” Ed said.

“Is it?” I wondered. But no one answered me.